There is a perception that Australia is a great country for children to grow up in. While certainly, Australia has some of the best nature and weather on offer, not all children are benefitting equally from this.

Unicef published a report on children’s wellbeing from rich countries. Australia scores 32 out of 38 on child well-being outcomes.

While it is hard to break down the exact causes for this low score, there are some more in-depth finding. For example there were strong links between happiness and the frequency of playing outside.

Researchers have found overwhelming evidence that neighbourhoods that encourage active travel have an high impact on physical and mental wellbeing. Walking and riding not only provides exercise but it is the only way to independently travel to places. Streets that are not safe for kids steal their independence. Freedom of choice is a significant factor in influencing children’s overall levels of subjective well-being

Last week the one of the most liked post in my local community Facebook page started with the following words: “We are a generation that will never come back. A generation that walked to school and back. A generation that did their homework alone to get out asap to play in the street. A generation that spent all their free time on the street. [..].”

My experience growing up in Germany in the 80’s was exactly like the above “Australian” experience. But interestingly, growing up in Germany has not changed as much like it has here: my 7-year old nephew walks to school unsupervised. And it is completely normal for kids to play on their local streets. Walking to school unsupervised from the age of 6 is encouraged by schools, local governments, road safety organizations and even the car lobby.

In Australia, it is almost the opposite. The NSW Centre for road safety recommends: “Children up to 10 should be supervised around traffic and should hold an adult’s hand when crossing the road.”

The Netherlands that scores highest on children wellbeing is famous for streets that are safe for people of all ages to enjoy – and for children to be independently travelling from a young age.

Cars and children are competitors in local streets. In Australia, we have chosen cars. Probably not on purpose but the result is visible. Most children are driven everywhere and not many children are allowed to play in their local streets. Usually, children spend their afternoons inactive if their parents don’t have time or money to drive them to afternoon activities. Australia has one of the lowest share of children walking or riding to school out of all OECD countries.

Since the 1970s the number of cars has increased by a factor 4 on Australian streets and not much has been done to reduce the negative consequences this has on our children who need to navigate traffic when walking to school or meeting friends. Countries like Germany and Sweden started introducing 30km/h speed limits in neighbourhoods in the 1980s. Drivers are expected to watch out for children and be ready to break in local streets. By making the streets safe for children to walk, there are less journeys made by car. Less traffic creates a better environment for children.

More often than we think we need to accept that change is necessary (like reducing urban speed limits from 50km/h to 30km/h) to keep things we value (children being active and independent).

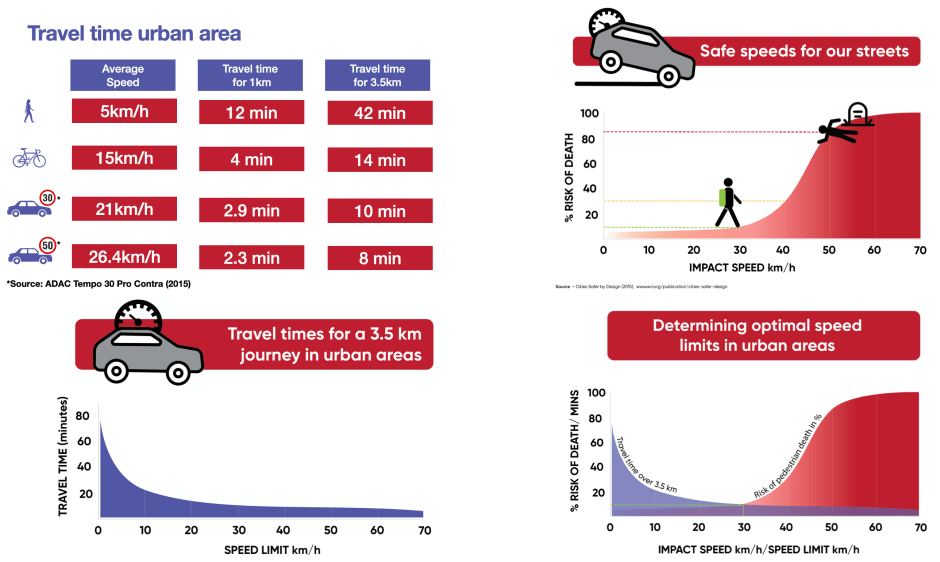

The tables below give an overview on travel time and safety impact of 30km/h speed limits:

In Australia, we have introduced tiny 40km/h speed zones around schools that are just big enough that children that are driven to school and need to walk to school from a parked car are not endangered by fast-moving cars. The school zones don’t do enough for children that walk home. Once children exit the school zone, drivers around them are reminded to speed up again to an unsafe speed of 50km/h or more. Many of the streets outside the school zones are simply too hard to cross for children which means they are not allowed to walk and are driven instead.

According to the NSW Centre for Road Safety, in a crash between a car and somebody walking, there is a 10 per cent risk that the person will be killed at 30 km/h, 40 per cent risk at 40 km/h, and a 90 per cent risk at 50 km/h.

Why do we expect drivers to slow down in school zones but find it too much to ask also to slow down where the children live?

Australian holiday parks provide an impressive example of the free-range, active childhood, kids in many northern European countries still enjoy. There are streets where kids are allowed to play, scoot or ride their bikes unsupervised. Here we find low-traffic, low-speed streets where drivers watch out and where parents feel confident in their children’s abilities to be independent outside without constant supervision even when surrounded by strangers.

We don’t need a large amount of expensive infrastructure in Australian neighbourhoods to create a better balance between children and cars, we need drivers to slow down and watch out more.

There would even be cheap in-car technology available that would stop us from exceeding the speed limit. In the EU all new cars are required to have a technology called Intelligent Speed Assist included, London buses use it already, why do we not request it here for all new cars? Do we think there is a right to exceed speed limits and put our most vulnerable road users in danger? Why would we let taxis, fleets and repeating speed offenders drive without this technology on board that is proven to save lives at a low cost?

To make our children happier, we should try to give our children back independence and encourage more incidental physical activity and unsupervised outdoor play.

We should aim for neighbourhoods where kids can meet their friends outside and explore, play on the streets and walk to school and afternoon activities.

One important step is to create a better balance in our neighbourhood streets and that means that here drivers will need to slow down to no more than 30km/h, the international best practice. An alliance of 13 Australian organisations including the Heart Foundation, the Australasian College for Road Safety, the Climate Council and the Telethon Kids Institute made “lower urban speed limits” the number one priority for transport for the 2022 federal election.

Will this make our kids more happy? Well it is not guaranteed but from all evidence that researchers have gathered it might be a good start.

Take action:

- Join WalkSydney

- Pledge your support to the #ThreeTransportPriorities

- Sign up as a supporter for Safe-Streets-to-School.org

You must be logged in to post a comment.